Decorated Plugins

When I think about how challenging it can be to read other developers’ code or even just one’s own code months later, I also think about how important it is to develop software with extensibility in mind from the start. So that’s why when working in python3, I’ve found myself using a pattern of providing a single location in the code where new plugins can be easily added, and a handy decorator that a developer can use for registering a plugin.

There’s lots of different ways to create a plugin architecture. The one we will develop in this post is lightweight, and mainly intended for a codebase which needs a clear way of extending typical functionalities. I’ve seen a similar pattern show up in neural network frameworks that allow developers to add new model architectures. We don’t have to be building a neural network framework to make use of this pattern, though, so let’s take a simpler example for our project. This project will be in python3.7.

Let’s say we’re processing a dataset of text files in some way, such as to replace extra symbols that are not useful for the task at hand. For example, we may want to add a rule to replace XML tags with some special token. We can do this in a naive (and madness inducing) way by using a regular expression [1]:

def replace_tags(sentence):

return re.sub(r'</?\w*?>', '<TAG>', sentence)Later in the development process, we may decide we also want to replace URLs in a similar way:

def replace_urls(sentence):

return re.sub(r'\w*?.(?:com|org)', '<URL>', sentence)Note: Both of these regexes will not work in any real situations, and you shouldn’t use them; I just wanted to have a short, stupid example for us to work with in this mini project.

We could just add all of these functions into a separate python module inside our codebase, and import them in whatever script we want to use them in. The drawbacks of that are that each time we want to add a new function to the process, we have to make sure that we import what we need and/or add it to whatever location makes the invocation.

Not only that, but if a new developer approaches the codebase for the first time, they have to understand how all these pieces and imports are put together before they can add their own replacer function, as well as how the inputs/outputs of the plugin should look. It’s much nicer if we can provide new developers a clear path to adding new functionality.

Concretely, we would like to:

- provide a consistent interface for plugins, that makes it clear what types of inputs/outputs they should have

- provide a clear way for developers to declare a function as a plugin

- automate the import of plugins, so the developer doesn’t have to figure out where they should go

- provide a simple user interface, which can be used to give different input sentences and select different plugins to use

There are a few different ways of achieving this, but I will focus on doing it with decorators. A decorator is basically just a function that takes another function as input, and returns a modified version of it. Python adds some extra syntactic sugar on top of this, using the @ symbol, which makes for a very clear and descriptive usage of decorators. What I like about them is that they make it clear as to the goals of the developer using them. They also allow decorated methods to be intermixed with other code, which is useful for our plugins, in case the plugins involves more complexity than just a simple function. I’ll show how it works a little further down the page.

Provide an interface

First, let’s start by creating a new abstract Plugin class, that will be used as an interface to the plugins we want to add:

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Plugin(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def __call__(self, input: str) -> str:

passThe abc package in python stands for “abstract base class.” This is a class specifically designed for inheriting from. Using @abstractmethod (another decorator) on a method in this class tells inheritors that they must implement the decorated method. If they don’t, a TypeError will be raised when attempting to instantiate the inheritor. The input: str and -> str are type hints, which are useful for telling the developer what the function’s inputs/outputs should look like.

Now, we can refactor our functions above into classes, that inherit from Plugin and implement the __call__() “magic method” (which allows the instance of a class to be invoked like a function):

class ReplaceTags(Plugin):

def __call__(self, sentence):

return re.sub(r'</?\w*?>', '<TAG>', sentence)

class ReplaceUrls(Plugin):

def __call__(self, sentence):

return re.sub(r'\w*?.(?:com|org)', '<URL>', sentence)By using this kind of interface, we are restricting the plugin developer from writing any arbitrary code to make the plugin work. This is useful, because now the main portion of our codebase knows exactly how to invoke the plugins that implement the Plugin interface. That is, it expects plugins to always look exactly the same. The plugin functionality is a little less flexible this way, but much more sane to work with.

Declaring plugins

Next, let’s provide developers with a way of declaring that some class should be used as a plugin. We’re going to give the developer a function that registers a plugin into a global dictionary. The dictionary will have plugin names for the keys, and the actual instantiated plugin classes for the values. This way, at runtime, we will just look up the desired plugins in the dictionary, by name, and invoke them in turn.

This is what the function that invokes the plugins at runtime will look like:

PLUGINS = {}

...

def process_sentence(sentence, plugin_names=[]):

"""

Process a sentence using the requested plugins.

>>> process_sentence("replace <xml> tags", ["replace_tags"])

'replace <TAG> tags'

"""

new_sentence = sentence

for name in plugin_names:

new_sentence = PLUGINS[name](new_sentence)

return new_sentenceIt really just takes a list of plugin names, that corresponds to the keys available in the PLUGINS dictionary, and invokes the callable located in the value of that dictionary.

Let’s look at how we can create a decorator to add callables into that dictionary. Actually, there are two ways to do this. The easy way, is to create a function which will be used as a decorator. This function will take a Plugin subclass, infer its name, instantiate it, and add it to the dictionary. At this point, it’s also nice to check for name collisions, so let’s also create a custom exception for that.

class NameConflictError(BaseException):

"""Raise for errors in adding plugins due to the same name."""

def register_plugin(plugin_class):

"""Register an instantiated plugin to the PLUGINS dict."""

name = plugin_class.__name__

if name in PLUGINS:

raise NameConflictError(

f"Plugin name conflict: '{name}'. Double check" \

" that all plugins have unique names.")

plugin = plugin_class()

PLUGINS[name] = plugin

return pluginWe could then use this function the verbose way, like this:

ReplaceTags = register_plugin(ReplaceTags)However, python provides us with a nice syntactic sugar for this in the form of the @ sign. The decorator can now be used with any Plugin sublcass, directly above the class, like so:

@register_plugin

class ReplaceTags(Plugin):

def __call__(self, sentence):

return re.sub(r'</?\w*?>', '<TAG>', sentence)In both cases, this decorator will augment our PLUGINS dictionary, so that it looks like this:

{

"ReplaceTags": instance_of_replace_tags

}However, if we want to use the dictionary keys in some kind of user interface later (there will be an example further down the page), we will want to give the user a more handy name to call the plugin, rather than the code-specific class name, which can become long or unintuitive. That is, we would like to be able to do something like this:

@register_plugin(name="replace_tags")

class ReplaceTags(Plugin):

def __call__(self, sentence):

return re.sub(r'</?\w*?>', '<TAG>', sentence)For this, we need to create a slightly more complicated decorator. The problem is that we can’t pass in both the decorated object and the extra decorator arguments, such as name, to decorators using the @ syntax. The reason for this has to do with the implementation of decorators themselves. Decorators are a class that take a callable in their __init__ constructor, and invoke the callable in their own __call__ method. If we give arguments to the constructor, the callable doesn’t get correctly passed in.

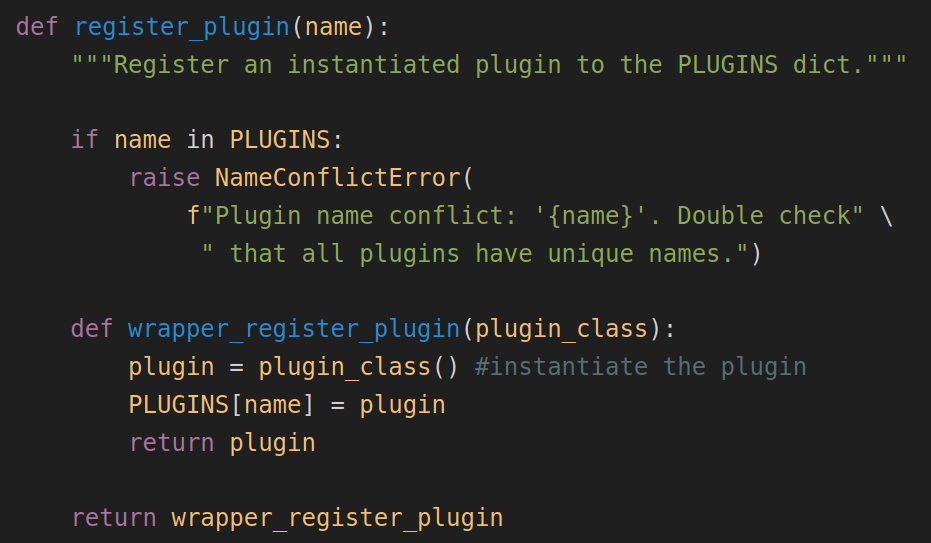

We can still use python’s decorators, we just have to be a little trickier with them. In this case, we are going to add an inner function to register_plugin. The outer function will now accept the single argument of name, while the inner function will wrap the Plugin, and return a modified version of it. Essentially, the inner function is the decorator wrapping the callable, and the outer function is another wrapper around that decorator.

def register_plugin(name):

"""Register an instantiated plugin to the PLUGINS dict."""

if name in PLUGINS:

raise NameConflictError(

f"Plugin name conflict: '{name}'. Double check" \

" that all plugins have unique names.")

def wrapper_register_plugin(plugin_class):

plugin = plugin_class() #instantiate the plugin

PLUGINS[name] = plugin

return plugin

return wrapper_register_pluginWhen we invoke the @register_plugin(name='replace_tags') we are doing nothing particularly special. We just invoke a function with some arguments. It just so happens though, that that function returns the inner wrapper_register_plugin function as an object (i.e. not invoked yet). The @ syntax then invokes the wrapper_register_function by passing in the one required argument of the ReplaceTags class, and the rest proceeds as normal. That is, ReplaceTags is instantiated, added to the PLUGINS dictionary, and returned as per usual.

All in all, this is similar to doing the following:

wrapper_register_plugin = register_plugin(name='replace_tags')

ReplaceTags = wrapper_register_plugin(ReplaceTags)Only, by doing it with the inner function, we get the benefit of a much clearer syntax for new developers adding plugins to our system.

@register_plugin(name="replace_tags")

class ReplaceTags(Plugin):

...Importing plugins

So far, we haven’t talked much about how all of these scripts we have can be organized. We could just have everything in one script, but this will quickly become unmaintainable. It would be better if plugins got their own directory, so it’s always clear to new developers where to add new functionality, but we would still like to prevent developers from having to know where to add imports. We want to make the architecture automatically find all of the decorated plugins.

For this piece of the puzzle, we need to know a little bit about python imports, which are not the most straightforward part of python. The most important part of all of this is that we (a) avoid circular imports, and (b) ensure that the PLUGINS dictionary gets populated with decorated plugins by the decorators before the rest of the code is executed– both when running our entrypoint script, and when importing our package.

We can do this by creating an __init__.py in our project. This file is the first file (except built-ins) that gets scanned for imports by the python interpreter. Adding an import statement at the top of this file ensures that the interpreter parses and loads those objects first:

import decoratorsNaturally, we then need to create decorators.py. This module will contain all of the decoration and importing machinery, like so:

import os

import importlib

WORKING_DIR = os.path.dirname(os.path.abspath(__file__))

PLUGINS = {}

class NameConflictError(BaseException):

...

def register_plugin(name):

...

def import_modules(dir_name):

"""Import all modules inside a directory."""

direc = os.path.join(WORKING_DIR, dir_name)

for f in os.listdir(direc):

path = os.path.join(direc, f)

if (

not f.startswith('_')

and not f.startswith('.')

and f.endswith('.py')

):

file_name = f[:f.find('.py')]

module = importlib.import_module(

f'{dir_name}.{file_name}')

import_modules("plugins") #stays outside main declarationThe import_modules function loops over all non-private modules (the ones that don’t start with _) in the plugins folder, and uses importlib to import them by name. Since decorators.py will never be called as a main module, we need to make sure that the import_modules function stays outside of the main declaraion (outside of if __name__ == '__main__') to ensure it gets invoked upon import of this file.

We want to keep all of this code together (i.e. don’t split up the dictionary from the decorators or the call to importlib). This is because we want to make sure that the interpreter does not follow a chain of imports out from here until after the PLUGINS dictionary is finished being filled.

User interface

Most of the code is finished, but it would be nice to provide a way for end-users to run the script without too much fuss. Of course, there are many very sophisticated UIs we can create, but for now, let’s just make a simple config file interface. The config file will provide us with an input text file, which has one sentence per line in it, and a list of processors, which will be the plugins. The script will read the input file line-by-line, call the processors on each line in the order the user provided, and then write the output to a new text file.

{

"input": "./data/input.txt",

"processors": ["replace_tags", "replace_urls"]

}The business logic code will live in our entrypoint script of run.py. I won’t detail all of it here, but I will just give a skeleton:

import os

import json

from decorators import PLUGINS

def process_sentence(sentence, plugin_names=[]):

"""

Process a sentence using the requested plugins.

>>> process_sentence("replace <xml> tags", ["replace_tags"])

'replace <TAG> tags'

"""

new_sentence = sentence

for name in plugin_names:

new_sentence = PLUGINS[name](new_sentence)

return new_sentence

def process_file(infile, outfile, processors):

"""

Process infile of one sentence per line.

Write the output to a new outfile.

"""

with open(infile, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as instream, \

open(outfile, 'w', encoding='utf-8') as outstream:

for i, line in enumerate(instream):

sentence = line.strip()

new_sentence = process_sentence(sentence, processors)

outstream.write(new_sentence + '\n')

def run(config_file):

"""

Parse a config file to get the input file path

and the list of processors. Apply processors

to sentences in the input file and save them to

a new output file with the `.processed` extension.

"""

with open(config_file, 'r', encoding='utf-8') as instream:

config = json.load(instream)

processors = config["processors"]

infile = config["input"]

outfile = infile + '.processed'

process_file(infile, outfile, processors)

def parse_args():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(

description="a mini plugin architecture")

parser.add_argument("config",

help="file path of json config file")

args = parser.parse_args()

if not os.path.exists(args.config):

raise FileNotFoundError(

f"config file not found: {args.config}")

return args

if __name__ == '__main__':

args = parse_args()

run(args.config)Directory structure

Our final directory structure, with all the code we have written so far, will look like this:

.

├── decorators.py

├── __init__.py

├── plugins

│ ├── plugins.py

└── run.pyThe decorators.py module will have:

PLUGINS: dictionary of plugin names to instantiated pluginsregister_plugin: decorator to add a plugin to the dictionarycollect_decorators: imports decorated plugins form subpackages

The __init__.py file will have

import decorators: early call to import this before everything else

The plugins.py module will have:

Plugin: abstract base class- decorated plugins (e.g.

ReplaceTags)

The run.py script will be our entrypoint, and it will have:

- an import of

PLUGINSat the top - the business logic

- argument parsing (although we can move it out if it gets big as well)

Summary

That’s it! We now have an extensible, mini (decorated) plugin architecture in python3. We covered a lot of concepts, including:

- interfaces for consistent plugin development

- decorators for registering plugins

- automating the import of decorated plugins

- making a config file for the end user

The original codebase for this blog post (plus a few extra functions) can be found at: https://github.com/kaleidoescape/decorated_plugins.git.

Footnotes

[1] XML is a structured markup language, which means it usually makes much more sense to use a proper XML parser to extract tags or portions of the data that you need. On the other hand, there may be times when you’re dealing with some strange use case, in which you have some deformed tags, outside of a structured document. I did have to do this once, but you should probably read this famous thread before following down this path of madness…. for me, it’s too late, but you may yet have a chance to save yourself!

Written on November 23, 2019. See a bug? Contact me on social (below).